The professionally accepted implant modalities with mainstream applications covered in this note are listed following box. Each of these modalities meets the scientific and clinical criteria for professional acceptance.These modalities are root forms, plate/blade forms, subperiosteals, endodontic stabilizers, and intramucosal inserts. Modalities that are not covered in this note may not lend themselves to mainstream applications because of clinical considerations such as excessive technique-sensitivity, need for treatment in a hospital environment, or insufficient data to demonstrate high long-term survival rates

Root forms

Plate/blade forms

Endodontic stabilizer

Unilateral subperiosteal implant

Intramucosal inserts

Adjusting plate/blade forms for enhanced parallelism at time of insertion

Bone growth within interconnecting porosities (left) of diffusion-bonded microsphere interface (right).

Root form transfer copings for direct impressioning at time of implant insertion

Stepped body design for insertion into immediate extraction site

CLASSIFICATION OF IMPLANT MODALITIES

Endosteal Implants

Endosteal implants comprise one broad category of implants. The most commonly applicable abutment providing modalities are endosteal. In mainstream cases, endosteal implants are placed within fully or partially edentulous alveolar ridges with sufficient residual available bone to accommodate the selected configuration.

Some endosteal implants are attached to components for the retention of a fixed or removable prosthesis. Other endosteal implants are equipped with an abutment integral with the implant body, which protrudes into the oral cavity during healing. Endosteal implant systems are commonly referred to as one-stage or two-stage. Sometimes these terms are used to describe the number of required surgical interventions. In this book, endosteal implant systems that require attachment of abutments or other attachment mechanisms at a visit subsequent to the insertion visit are referred to as two-stage, and those that are equipped with an integral abutment at the time of insertion are referred to as one-stage. Therefore, what some manufacturers call “one-stage,” meaning that only one surgical intervention is required, is what this book refers to as the two-stage semi-submersion healing option, in which a healing collar is placed flush with or up to 1 mm above the gingiva at the time of implant placement, thus avoiding the implant exposure surgery associated with submersion under the gingiva at the time of implant insertion.

Root Forms.

Root form implants are designed to resemble the shape of a natural tooth root. They usually are circular in cross section. Root forms can be threaded, smooth, stepped, parallel-sided or tapered, with or without a coating, with or without grooves or a vent, and can be joined to a wide variety of components for retention of a prosthesis.

As a rule, root forms must achieve osteointegration to succeed. Therefore, they are placed in an afunctional state during healing until they are osteointegrated. Semi-submerged implant healing collars are then removed, or submerged implants are surgically exposed for the attachment of components for the retention of a fixed or removable prosthesis. Thus, most root forms are two-stage implants. Stage one is submersion or semi-submersion to permit afunctional healing , and stage two is the attachment of an abutment or retention mechanism. Semi-submersion of root forms obviates the need for two surgical interventions, which represents an important improvement in the modality in terms of technique-permissiveness. Root form protocols require separate treatment steps for insertion and abutment or retention mechanism attachment whether the healing protocol calls for submersion or semi-submersion.

First-stage submerged (cover screws, above) and semi-submerged (healing collars, below) healing options to achieve osteointegration.

Second-stage prosthesis attachment mechanism following healing

A root form can be placed anywhere in the mandible or maxilla where there is sufficient available bone. However, because of the diameter of root form implants, most mainstream treatment involves anterior insertion for single-tooth replacement or restoration with overdentures. With the innovation of the diffusion-bonded microsphere interface, the mainstream applicability of this modality has increased in cases of posterior partial edentulism requiring five or fewer units of restorative dentistry. Tapered smooth and threaded cylinders also are fine choices for anterior edentulism. Following figures show typical mainstream root form cases.

Root forms to support single-tooth replacements

Crowns individually supported by root forms

Root form-supported single-tooth replacement in mandible

Splinted root forms with coping bar for overdenture retention.

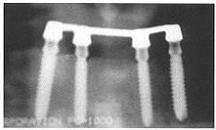

Plate/Blade Forms

As its name suggests, the basic shape of the plate/blade form implant is similar to that of a metal plate or blade in cross-section. Some plate/blade forms have a combination of parallel and tapered sides. Just as screws and cylinders are both of the root form modality, plate forms and blade forms are both of the plate/blade form modality. Plate/blade form systems are supplied in one-stage and two-stage varieties. One-stage plate/blade form implants are fabricated of one solid piece of titanium, with the abutment contiguous with the body of the implant. Two-stage plate/blade form implants are supplied with detachable abutments and healing collars. The one-stage and two-stage options exist so the practitioner can use the osteointegration or osteopreservation mode of tissue integration, according to the needs of the case.

Profiles of Generation Ten and Standard plate/blade form implants

Three-dimensional finite element model of plate/blade form with combination of parallel and tapered sides in a mandible

One-stage (above) and two-stage (below) plate/blade form options

Plate/blade forms are unique among implants in that they can function successfully in either the osteointegration or osteopreservation mode of tissue integration. When mainstream protocols are followed, one-stage implants heal in the osteopreservation mode of tissue integration, and two-stage implants osteointegrate. As with two-stage root forms, two-stage plate/blade forms require a second treatment step for the attachment of abutments. However, two-stage plate/blade forms are designed to heal in the semi-submerged healing mode, so the second-stage removal of the healing collar and attachment of the abutment does not require a surgical intervention.

As with root form implants, plate/blade form implants can be placed anywhere in the mandible or maxilla where there is sufficient available bone. However, because of their narrower bucco/labio-lingual width, plate/blade forms tend to be applicable in a wider range of available bone presentations, especially in the posterior of the ridges. Plate/blade forms can be used for the majority of implant dentistry candidates, and in 100% of cases in which root forms can be inserted.

Three-unit fixed bridge supported by plate/blade form with natural co-abutment in mandible

Five-unit fixed bridge with interdental plate/blade form support

Endodontic Stabilizer Implants

Although endodontic stabilizer implants are endosteal implants, they differ from other endosteal implants in terms of functional application. Rather than providing additional abutment support for restorative dentistry, they are used to extend the functional length of an existing tooth root to improve its prognosis and when required, its ability to support bridgework. Modern endodontic stabilizers take the form of a long, threaded post that passes at least 5 mm beyond the apex of the tooth root into available bone. Endodontic stabilizers have been designed with parallel or tapered sides, smooth or threaded. The most successful endodontic stabilizers are threaded and parallel-sided, with sluiceways in the threaded crests that prevent apical cement sealant from being expressed into bone by guiding it crestally. The parallel-sided threaded design controls the stress concentration at the apex of the root, protecting against fracture and trauma.

The endodontic stabilizer functions in the osteopreservation mode of tissue integration, because the tooth root through which it is inserted is subjected to normal physiologic micromovement as it heals. Endodontic stabilizers are placed and the procedure is completed in one visit, as the final step of any conventional endodontic regimen.

The range of applicability of the endodontic stabilizer is dictated by the need for at least 5 mm of available bone beyond the apex of the tooth being treated, and the need to avoid certain anatomic landmarks. Five millimeters of available bone is the minimum that can increase the crown-root ratio to an extent sufficient to affect positively the prognosis of the tooth. In the mandible, the first premolar and the teeth anterior to it are good candidates for endodontic stabilization. The second premolar and molars are over the inferior alveolar canal, and therefore are usually not good candidates for mainstream endodontic stabilization. In the maxilla, the teeth most often treated are the centrals, laterals, cuspids, and the lingual root of first premolars. The second premolar and molars are under the maxillary sinus, and therefore usually are not good candidates for mainstream endodontic stabilization.

Endodontic stabilizers lengthening tooth roots in anterior mandible

Endodontic stabilizer lengthening tooth roots in anterior maxilla.

Ramus Frame Implants

Ramus frame implants have been demonstrated to be safe and effective. They are intended for the treatment of total mandibular edentulism with severe alveolar ridge resorption. Ramus frame implants do not have mainstream applications because of technique-sensitivity. They feature an external attachment bar that courses a few millimeters superior to the crest of the ridge from ascending ramus to ascending ramus. Posteriorly on each side, an endosteal extension inserts into available bone within each ascending ramus. Anteriorly, the bar is contiguous with a plate/blade form type of extension that is inserted into available bone in the symphyseal area.

Mandibular ramus frame implant with overdenture.

Transosteal Implants

Among endosteal implants, transosteal implants are the most surgically invasive and technique-sensitive. As with ramus frame implants, they are limited to the mandible. Although transosteal implants have proven safety and efficacy, they are not considered mainstream because of their complexity and the demands they make on both the practitioner and the patient. Transosteal implants feature a plate that is placed against the exposed inferior border of the mandible, with extensions that pass from this plate through the symphyseal area, out of the crest of the ridge, and into the oral cavity.This is usually a hospital-based procedure.

Presentation model of transosteal implant

Subperiosteal Implants

The subperiosteal implant modality is distinct from the endosteal implant modalities in that the implant is placed under the periosteum and against bone on the day of insertion, rather than within alveolar bone. This modality is used in cases of advanced alveolar resorption, in which the volume of the residual available bone is insufficient for the insertion of an endosteal implant.The subperiosteal implant is retained by periosteal integration, in which the outer layer of the periosteum provides dense fibrous envelopment and anchors the implant to bone through Sharpey’s fibers, and also by retentive undercut features of the implant design. Subperiosteal implants are custom-made and are of four types. Unilateral subperiosteal implants usually are placed in severely resorbed premolar and molar areas of the mandible or maxilla, where there are no distal natural abutments.

Unilateral subperiosteal implant in mandible.

Unilateral subperiosteal implant in maxilla

An interdental subperiosteal implant spans a severely resorbed edentulous area between remaining natural teeth. These implants can be used anteriorly or posteriorly in either arch. They are rarely indicated but nonetheless are considered mainstream in the rare cases in which they are applicable.

Interdental subperiosteal implant in anterior maxilla.

Total subperiosteal implants are for patients who have lost all of their teeth in one arch. Such treatment is not considered mainstream but can be performed after experience with a number of unilateral or interdental cases.

Total mandibular subperiosteal implant.

Finally, a circumferential subperiosteal is a modification of a total subperiosteal implant but is used in cases in which several anterior teeth are still in position. Circum-ferential subperiosteal cases are most often mandibular. The lingual and buccal main bearing struts are designed such that the connecting struts are distal to the last natural tooth on each side, allowing the entire implant to pass over the anterior teeth to rest against basal bone. The circumferential subperiosteal is akin to two unilateral subperiosteals that are connected with anterior labial and lingual main bearing struts.

In mainstream unilateral subperiosteal treatment, two surgical interventions are required—the first to take a direct bone impression to obtain a model from which the custom-made implant is fabricated, and the second to place the implant. Although the application of computer-generated bone modeling is promising , it is not yet considered to be a mainstream technique for obtaining an accurate bone model in unilateral cases.

Intramucosal Inserts

Intramucosal inserts differ in form, concept, and function from the other modalities. They are mushroom-shaped titanium projections that are attached to the tissue surface of a partial or total removable denture in the maxilla[14] and plug into prepared soft-tissue receptor sites in the gingiva to provide additional retention and stability. Thus, they provide support for a prosthesis but do not provide abutments. They are used in the treatment of patients for whom endosteal or subperiosteal implants are not deemed to be practical or desirable.

Intramucosal inserts do not come into contact with bone, so the mode of tissue integration is not osteointegration, osteopreservation, or periosteal integration. Rather, the receptor sites in the tissue into which the inserts seat become lined with tough, keratinized epithelium. In this sense, seated intramucosal inserts are external to the body. Only one appointment is required for the placement of intramucosal inserts.

Intramucosal inserts are best used in the maxilla. Because of complicated biomechanics, more acute alveolar ridge angles, a wider array of applied forces, and insufficient gingival thickness, placement of intramucosal inserts in the mandible is not recommended.

Large intramucosal inserts in position

Standard intramucosal inserts in position