Anatomy and microstructure of periodontium

This includes a brief description of the characteristics of the normal periodontium. It is assumed that the reader has prior knowledge of oral embryology and histology.

The periodontium (pert = around, odontos = tooth) comprises the following tissues

(1) Gingiva (G)

(2) Periodontal ligament (PL)

(3) Root cementum (RC)

(4) Alveolar bone(AB)- The alveolar bone consists of two components

Alveolar bone proper

Alveolar process

The main function of the periodontium is to attach the tooth to the bone tissue of the jaws and to maintain the integrity of the surface of the masticatory mucosa of the oral cavity.

The development of the periodontal tissues occurs during the development and formation of teeth. This process starts early in the embryonic phase when cells from the neural crest (from the neural tube of the embryo) migrate into the first branchial arch. During the cap stage, condensation of ectomesenchymal cells appears in relation to the dental epithelium (the dental organ (DO)), forming the dental papilla (DP) that gives rise to the dentin and the pulp, and the dental follicle (DF) that gives rise to the periodontal supporting tissues.

The development of the root and the periodontal supporting tissues follows that of the crown. Epithelial cells of the external and internal dental epithelium (the dental organ) proliferate in apical direction forming a double layer of cells named Hertwig's epithelial root sheath (RS). The odontoblasts (OB) forming the dentin of the root differentiate from ectomesenchymal cells in the dental papilla under inductive influence of the inner epithelial cells.

GINGIVA

Macroscopic anatomy

The gingiva is that part of the masticatory mucosa which covers the alveolar process and sur-rounds the cervical portion of the teeth. It consists of an epithelial layer and an underlying connective tis-sue layer called the lamina propria. The gingiva obtains its final shape and texture in conjunction with eruption of the teeth.

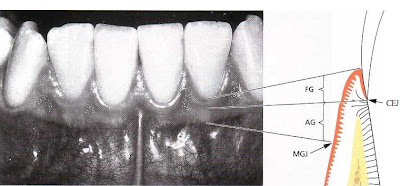

In the coronal direction the coral pink gingiva terminates in the free gingival margin, which has a scalloped outline. In the apical direction the gingiva is continuous with the loose, darker red alveolar mucosa (lining mucosa) from which the gingiva is separated by a, usually, easily recognizable borderline called either the mucogingival junction or the mucogingival line. There is no mucogingival line present in the palate since the hard palate and the maxillary alveolar process are covered by the same type of masticatory mucosa.

Two parts of the gingiva can be differentiated:

1. the free gingiva (FG)

2. the attached gingiva (AG)

On the vestibular and lingual side of the teeth, the free gingiva extends from the gingival margin in apical direction to the free gingival groove which is positioned at a level corresponding to the level of the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). The attached gingiva is in apical direction demarcated by the mucogingival junction (MGJ).

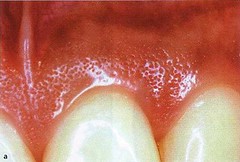

The attached gingiva extends in the apical direction to the mucogingival junction (arrows), where it be-comes continuous with the alveolar (lining) mucosa (AM). It is of firm texture, coral pink in color, and often shows small depressions on the surface. The depressions, named "stippling", give the appearance of orange peel.

Microscopic anatomy

The free gingiva comprises all epithelial and connective tissue structures (CT) located coronal to a horizontal line placed at the level of the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). The epithelium covering the free gingiva may be differentiated as follows:

Oral epithelium (OE), which faces the oral cavity

Oral sulcular epithelium (OSE), which faces the tooth without being in contact with the tooth surface

Junctional epithelium (JE), which provides the contact between the gingiva and the tooth.

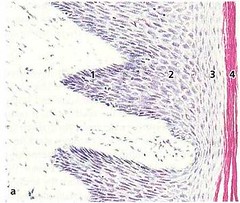

The boundary between the oral epithelium (OE) and the underlying connective tissue (CT) has a wavy course. The connective tissue portions which project into the epithelium are called connective tissue papillae (CTP) and are separated from each other by epithelial ridges — so-called rete pegs (ER). In normal non-inflamed gingiva, rete pegs and connective tissue papillae are lacking at the boundary between the junctional epithelium and its underlying connective tissue.

Portion of the oral epithelium covering the free gingival is a keratinized, stratified, squamous epithelium which, on the basis of the degree to which the keratin-producing cells are differentiated, can be divided into the following cell layers:

1. basal layer (stratum basale or stratum germinativum)

2. prickle cell layer (stratum spinosum)

3. granular cell layer (stratum granulosum)

4. keratinized cell layer (stratum corneum)

PERIODONTAL LIGAMENT

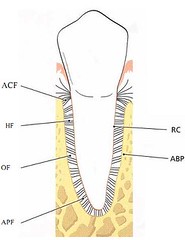

The periodontal ligament is the soft, richly vascular and cellular connective tissue which surrounds the roots of the teeth and joins the root cementum with socket wall. In the coronal direction, the periodontal ligament is continuous with the lamina propria of the gingiva and is demarcated from the gingiva by the collagen fiber bundles which connect the alveolar bone crest with the root (the alveolar crest fibers).

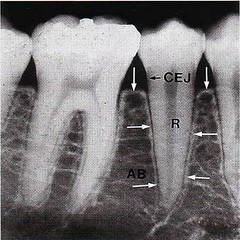

In radiographs, two types of alveolarbone can be distinguished:

1. The part of the alveolar bone which covers the alveolus, called "lamina dura" (arrows).

2. The portion of the alveolar process which, in the radiograph, has the appearance of a meshwork. This is called the "spongy bone".

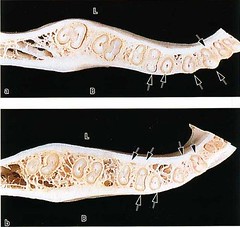

The periodontal ligament is situated in the space be-tween the roots (R) of the teeth and the lamina dura or the alveolar bone proper (arrows). The alveolar bone (AB) surrounds the tooth to a level approximately 1mm apical to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). The coronal border of the bone is called the alveolar crest (arrows).

The width of the periodontal ligament is approximately 0.25 mm (range 0.2-0.4 mm). The presence of a peri-odontal ligament permits forces, elicited during mas-ticatory function and other tooth contacts, to be dis-tributed to and resorbed by the alveolar process via the alveolar bone proper. The periodontal ligament is also essential for the mobility of the teeth. Tooth mo-bility is to a large extent determined by the width, height and quality of the periodontal ligament.

The tooth is joined to the bone by bundles of collagen fibers which can be divided into the following main groups according to their arrangement:

1. alveolar crest fibers (ACF)

2. horizontal fibers (HF)

3. oblique fibers (OF)

4. apical fibers (APF)

ROOT CEMENTUM

The cementum is a specialized mineralized tissue covering the root surfaces and, occasionally, small portions of the crown of the teeth. It has many features in common with bone tissue. However, the cementum contains no blood or lymph vessels, has no innervation, does not undergo physiologic resorption or remodeling, but is characterized by continuing deposition throughout life. Like other mineralized tissues, it contains collagen fibers embedded in an organic matrix. Its mineral content, which is mainly hydroxyapatite, is about 65% by weight; a little more than that of bone (i.e. 60%). Cementum serves different functions. It attaches the periodontal ligament fibers to the root and contributes to the process of repair after damage to the root surface.

Different forms of cementum have been described:

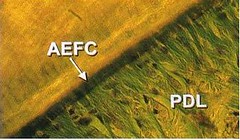

Acellular, extrinsic fiber cementum (AEFC)- is found in the coronal and middle portions of the root and contains mainly bundles of Sharpey's fibers. This type of cementum is an important part of the attachment apparatus and connects the tooth with the alveolar bone proper.

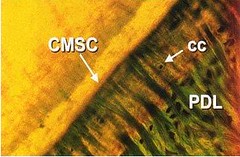

Cellular, mixed stratified cementum (CMSC)- occurs in the apical third of the roots and in the furcations. It contains both extrinsic and intrinsic fibers as well as cementocytes.

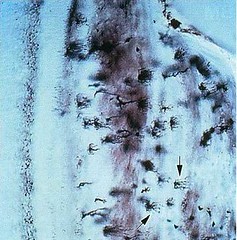

Cellular, intrinsic fiber cementum (CIFC)- is found mainly in resorption lacunae and it contains intrinsic fibers and cementocytes.

ALVEOLAR BONE

The alveolar process is defined as the parts of the maxilla and the mandible that form and support the sockets of the teeth. The alveolar process develops in conjunction with the development and eruption of the teeth. The alveolar process consists of bone which is formed both by cells from the dental follicle (alveolar bone proper) and cells which are independent of tooth development. Together with the root cementum and the periodontal membrane, the alveolar bone consti-tutes the attachment apparatus of the teeth, the main function of which is to distribute and resorb forces generated by, for example, mastication and other tooth contacts.

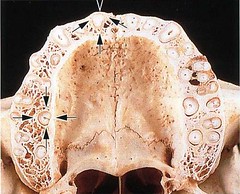

The walls of the sockets are lined by cortical bone (arrows), and the area between the sockets and between the compact jaw bone walls is occupied by cancellous bone. The cancel-lous bone occupies most of the interdental septa but only a relatively small portion of the buccal and pala-tal bone plates. The cancellous bone contains bone trabeculae, the architecture and size of which are partly genetically determined and partly the result of the forces to which the teeth are exposed during function. Note how the bone on the buccal and palatal aspects of the alveolar process varies in thickness from one region to another. The bone plate is thick at the palatal aspect and on the buccal aspect of the molars but thin in the buccal anterior region.

BLOOD SUPPLY OF THE PERIODONTIUM

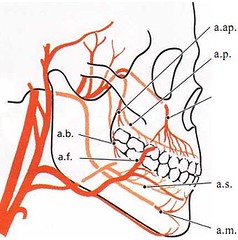

fig

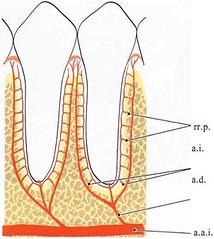

The dental artery (a.d.), which is a branch of the superior or inferior alveolar artery (a.a.i.), dismisses the intraseptal artery (a.i.) before it enters the tooth socket. The terminal branches of the intraseptal artery (rami perforantes, rr.p.) penetrate the alveolar bone proper in canals at all levels of the socket (see Fig. 1-76). They anastomose in the periodontal ligament space, together with blood vessels originating from the apical portion of the periodontal ligament and with other terminal branches, from the intraseptal artery (a.i.). Before the dental artery (a.d.) enters the root canal it puts out branches which supply the apical portion of the periodontal ligament.

The gingiva receives its blood supply mainlythrough supraperiosteal blood vessels which are terminal branches of the sublingual artery (a.s.), the mental artery (a.m.), the buccal artery (a.b.), the facial artery (a.f.), the greater palatine artery (a.p.), the infra orbital artery (a.i.) and the posterior superior dental artery(a.ap.).

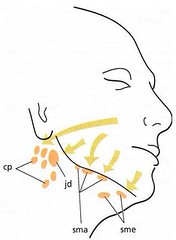

LYMPHATIC SYSTEM OF THE PERIODONTIUM

The smallest lymph vessels, the lymph capillaries, form an extensive network in the connective tissue. The wall of the lymph capillary consists of a single layer of endothelial cells. For this reason such capillaries are difficult to identify in an ordinary histologic section. The lymph is absorbed from the tissue fluid through the thin walls into the lymph capillaries. From the capillaries, the lymph passes into larger lymph vessels which are often in the vicinity of corresponding blood vessels. Before the lymph enters the blood stream it passes through one or more lymph nodes in which the lymph becomes filtered and supplied with lymphocytes. The lymph vessels are like veins provided with valves. The lymph from the periodontal tissues is drained to the lymph nodes of the head and the neck. The labial and lingual gingiva of the mandibular incisor region is drained to the submental lymph nodes (sme). The palatal gingiva of the maxilla is drained to the deep cervical lymph nodes (cp). The buccal gingiva of the maxilla and the buccal and lingual gingiva in the mandibular premolar-molar region are drained to submandibular lymph nodes (sma).

Except for the third molars and mandibular incisors, all teeth with their adjacent periodontal tissues are drained to the submandibular lymph nodes (sma). The third molars are drained to the jugulodigastric lymph node (jd) and the mandibular incisors to the submental lymph nodes (sme).

NERVES OF THE PERIODONTIUM

Like other tissues in the body, the periodontium contains receptors which record pain, touch and pressure (nociceptors and mechanoreceptors). In addition to the different types of sensory receptors, nerve compo-nents are found innervating the blood vessels of the periodontium. Nerves recording pain, touch, and pressure have their trophic center in the semilunar ganglion and are brought to the periodontium via the trigeminal nerve and its end branches. Owing to the presence of receptors in the periodontal ligament, small forces applied on the teeth may be identified. For example, the presence of a very thin (10-30 µm) metal foil (strip) placed between the teeth during occlusion can readily be identified. It is also well known that a movement which brings the teeth of the mandible in contact with the occlusal surfaces of the maxillary teeth is arrested reflexively and altered into an opening movement if a hard object is detected in the chew. Thus, the receptors in the periodontal liga-ment, together with the proprioceptors in muscles and tendons, play an essential role in the regulation of chewing movements and chewing forces.

Excellently described, thanks, Subhash

ReplyDeleteI’m really impressed with your article, such great & usefull knowledge you mentioned here top dentistry schools

ReplyDeleteI was diagnosed as HEPATITIS B carrier in 2013 with fibrosis of the

ReplyDeleteliver already present. I started on antiviral medications which

reduced the viral load initially. After a couple of years the virus

became resistant. I started on HEPATITIS B Herbal treatment from

ULTIMATE LIFE CLINIC (www.ultimatelifeclinic.com) in March, 2020. Their

treatment totally reversed the virus. I did another blood test after

the 6 months long treatment and tested negative to the virus. Amazing

treatment! This treatment is a breakthrough for all HBV carriers.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteWhat really caught my attention is how precise the periodontal ligament is described, especially its role in sensing tiny forces. It makes you realize how sensitive and smart this system is. Reading this reminded me of explanations I once heard at madison dental forest hills ny—suddenly the anatomy feels very real.

ReplyDelete